The decline of the Mughal Empire was a complex, multi-dimensional, and gradual process. It began soon after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 and culminated in the removal of the last emperor Bahadur Shah II in 1858 after the Revolt of 1857.

Historians describe it as a decline caused by internal decay + external pressures + structural weaknesses.

The decline of the Mughal Empire was a complex process influenced by a combination of internal and external factors. Here’s a breakdown of some of the key reasons:

The Erosion of Central Authority

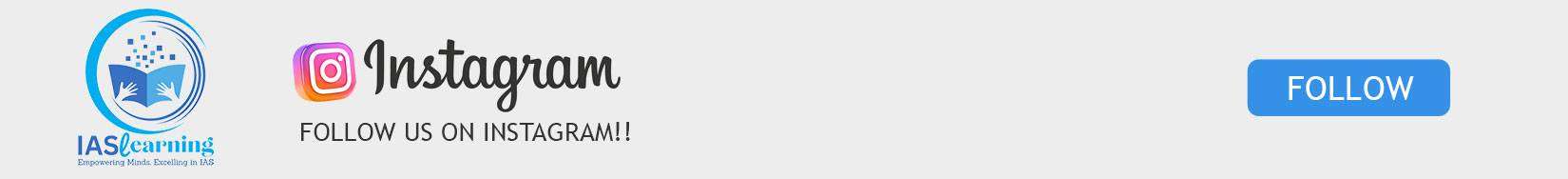

The death of Aurangzeb in 1707 marked a pivotal turning point, ushering in an era often referred to as the “Later Mughals.” This period was characterized by a dramatic decline in the quality of leadership, which directly contributed to the empire’s fragmentation and eventual collapse. The imperial throne became a revolving door for weak, indecisive, and often pleasure-seeking rulers, whose lack of vision and administrative capabilities paved the way for internal decay and external interference.

Economic Drain: The continuous court extravagance, coupled with the heavy indemnity paid to Nadir Shah, severely depleted the imperial treasury, leaving the empire without resources to defend itself or effectively administer its remaining territories.

Weak and Incompetent Successors:

Bahadur Shah I (1707–1712)

Initial Hopes, Limited Impact: After a brief but intense war of succession, Bahadur Shah I, also known as Shah Alam I, ascended the throne. He initially attempted to reverse some of Aurangzeb’s more divisive policies. He adopted a more conciliatory approach towards the Rajputs, granting them high offices and not directly interfering in their internal affairs. He also made efforts to negotiate with the Sikhs, though these were ultimately unsuccessful as conflicts re-emerged under Banda Bahadur.

Lack of Firmness: Despite these attempts at reconciliation, Bahadur Shah I lacked the firm hand and decisive leadership required to consolidate power. He was often criticized for his indecisiveness, earning him the nickname “Shah-i-Bekhabar” (the Heedless King). His policies were often inconsistent, and he failed to address the burgeoning financial crisis or the growing assertiveness of provincial governors. The jizya tax, abolished by Akbar, was nominally re-imposed but rarely collected, indicating the state’s growing weakness rather than a firm policy.

Financial Drain: His reign also saw an increase in the number of nobles and jagirs (revenue assignments), exacerbating the already strained imperial finances. The generosity, or rather weakness, in granting jagirs without sufficient lands available led to a crisis known as the Jagirdari Crisis, a fundamental structural flaw that worsened significantly after his rule.

Jahandar Shah (1712–1713)

Puppet of Favorites: Jahandar Shah’s reign was exceptionally brief and infamous for its excesses. He was a frivolous ruler, largely controlled by his powerful Wazir (prime minister), Zulfiqar Khan, and his favorite concubine, Lal Kunwar (often referred to as Lal Kumari).

Indulgence and Neglect: His court was characterized by lavish parties, extravagance, and a complete neglect of state affairs. Important administrative decisions were often swayed by personal whims and the influence of his favorites, rather than sound judgment. This indulgence further eroded the prestige and moral authority of the Mughal throne.

Zulfiqar Khan’s Reforms (and failures): While Jahandar Shah himself was incompetent, his Wazir, Zulfiqar Khan, attempted some administrative reforms, such as the ijara system (revenue farming) to generate income. However, these short-term solutions often led to greater exploitation of the peasantry and did not address the root causes of the financial crisis. Zulfiqar Khan also tried to forge alliances with the Marathas by granting them Chauth (one-fourth of the revenue) and Sardeshmukhi (an additional one-tenth) in the Deccan, but this effectively acknowledged Maratha power and legitimized their claims, further weakening imperial control.

Farrukhsiyar (1713–1719)

Rise of the “Kingmakers” – The Sayyid Brothers: Farrukhsiyar’s ascension was engineered by the powerful Sayyid Brothers, Abdullah Khan and Hussain Ali Khan Barha, who became the de facto rulers of the empire. They were brilliant administrators and military commanders, but their primary loyalty was to their own power rather than the integrity of the Mughal state.

Weak-Willed and Paranoid: Farrukhsiyar proved to be a weak, indecisive, and paranoid ruler, constantly fearing plots against him and frequently attempting to undermine the Sayyid Brothers who had placed him on the throne. His attempts to rid himself of their influence ultimately backfired.

Concessions to the British: It was during Farrukhsiyar’s reign that the infamous Farman (royal decree) of 1717 was issued, granting the British East India Company significant trading privileges in Bengal, including duty-free trade and the right to mint coins. This “Magna Carta of the Company,” as it’s often called, gravely undermined Mughal sovereignty and revenues in Bengal and laid the groundwork for future British dominance.

Deposition and Assassination: His constant intrigues led the Sayyid Brothers, in an unprecedented move, to depose and eventually blind and assassinate him. This act sent shockwaves through the empire, demonstrating that the emperor was no longer sacrosanct and could be made and unmade by powerful nobles. It further degraded the prestige and sanctity of the imperial office.

Muhammad Shah ‘Rangeela’ (1719–1748)

“The Colourful” Emperor: Muhammad Shah earned the epithet “Rangeela” (the Colourful or the Joyous) due to his devotion to pleasure, fine arts, music, and poetry, often to the complete exclusion of state affairs. He spent most of his time in pursuit of personal entertainment, allowing the administration to largely run itself or be managed by ambitious nobles.

Decline of Court Patronage and Morale: While his reign saw a flowering of certain artistic pursuits, it coincided with a severe decline in administrative efficiency and moral standards at court. Factionalism among nobles reached new heights, with groups constantly vying for power and wealth, often at the expense of imperial interests.

Further Rise of Autonomous States: With the emperor disengaged, provincial governors like Murshid Quli Khan (Bengal), Saadat Khan (Awadh), and Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I (Hyderabad) consolidated their power and effectively established autonomous states, though they often maintained a nominal allegiance to the Mughal emperor. This period truly saw the empire transform into a collection of independent regional powers.

Nadir Shah’s Invasion (1739): The most devastating blow during Muhammad Shah’s reign was the invasion of Nadir Shah of Persia. Taking advantage of the empire’s political and military weakness, Nadir Shah marched into India, defeated the Mughal army at Karnal, sacked Delhi, and carried away immense wealth, including the Peacock Throne and the Koh-i-Noor diamond. This invasion not only drained the empire’s treasury but also shattered its remaining prestige and revealed its utter vulnerability to foreign attack. It marked a definitive end to any illusion of Mughal invincibility.

You’ve hit on another critical internal cause: the debilitating effect of Court Factionalism and the Rise of Powerful Nobles. This internal strife was a direct consequence of weak central authority and, in turn, further accelerated the empire’s decline.

Court Factionalism and the Rise of Powerful Nobles

The Mughal court, once a centralized hub of power and a meritocracy under strong emperors, transformed into a hotbed of intrigue and rivalries after Aurangzeb. With weak emperors on the throne, the real power shifted to ambitious nobles who often prioritized their personal and factional interests over the welfare of the empire. This led to chronic instability, a breakdown of administration, and a further erosion of the emperor’s authority.

- Diverse Factions within the Mughal Nobility: The Mughal nobility was a composite body, deliberately kept diverse by earlier emperors to prevent any single group from becoming too powerful. However, in the absence of strong imperial control, these diverse groups coalesced into powerful, self-interested factions:

- Iranis (Persians): These nobles were largely Shia Muslims and often held high administrative and financial posts due to their long tradition of sophisticated bureaucracy in Persia. They brought with them distinct cultural and administrative practices. Prominent examples include Mir Qamar-ud-din Siddiqi (Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I, who later founded the independent state of Hyderabad) and his father Ghazi-ud-din Khan Feroz Jung I. Their wealth and cultural influence were significant.

- Turanis (Central Asians): Comprising Sunni Muslims of Turkic origin, often from Transoxiana (Turan), they represented the traditional military backbone of the Mughal Empire and claimed a lineage similar to the Mughals themselves. They held key military commands and often resented the rising influence of Iranis. Feroz Jung III and his son Ghazi-ud-din Imad-ul-Mulk were notable Turanis.

- Hindustanis: This faction comprised Indian-born Muslims (many of whom converted from Hinduism) and Hindu Rajputs. They were intimately familiar with local conditions and often commanded significant indigenous support. While some Rajputs had historically been allies, the later Mughals’ policies often strained these relationships. The Sayyid Brothers are the most famous example of this faction, having deep roots in India.

- Afghans: A smaller but potent group, often serving as fierce soldiers and local chieftains. They frequently sought to establish their own independent principalities, particularly in regions like Rohilkhand (Rohillas), and were often seen as formidable, if sometimes rebellious, elements within the empire.

- Control over the Emperor: Each faction sought to install a puppet emperor or gain dominant influence over the reigning monarch to further their agenda.

- Key Appointments: The Wizarat (Prime Ministership), Mir Bakshi (head of military administration), and Diwan (head of finance) were the most coveted positions, as they controlled patronage, resources, and policy.

- Jagirs and Mansabs: Jagirs (revenue assignments from specific territories) and Mansabs (military and administrative ranks) were the lifeblood of the nobility. Control over these meant wealth, influence, and the ability to maintain a loyal retinue of soldiers. The scarcity of profitable jagirs, exacerbated by the Jagirdari Crisis, intensified this competition.

- The Sayyid Brothers (“King Makers”):

- Ascendance to Unprecedented Power: Abdullah Khan and Hussain Ali Khan Barha, known collectively as the Sayyid Brothers, exemplified the extreme extent of factional power. Belonging to the Hindustani faction, they rose to prominence in the early 18th century, leveraging their military skill and political acumen.

- Installation and Dethronement of Emperors (1713–1720): Their most striking achievement was their role as “kingmakers.” They were instrumental in the ascension of Farrukhsiyar in 1713. When Farrukhsiyar tried to assert his independence, they brutally deposed and murdered him in 1719 – an unprecedented act that shattered the sanctity of the imperial office. They subsequently installed a series of short-lived puppet emperors (Rafi-ud-Darajat, Rafi-ud-Daula) before placing Muhammad Shah ‘Rangeela’ on the throne.

- Demonstration of Mughal Throne’s Weakness: The Sayyid Brothers’ dominance unequivocally demonstrated that the Mughal emperor had become a mere figurehead, a pawn in the hands of powerful nobles. The ability of a faction to make and unmake emperors stripped the throne of its divine aura and moral authority, making it clear to both internal and external observers that the central power was broken.

- Policies and Downfall: While they attempted to stabilize the empire by forging alliances (e.g., with the Marathas and Rajputs) and introducing some administrative measures, their primary objective remained their own power. Their autocratic style and constant intrigues eventually led to a powerful counter-faction, led by Turani nobles like Nizam-ul-Mulk, conspiring against them. Hussain Ali Khan was assassinated in 1720, and Abdullah Khan was defeated and imprisoned shortly after, bringing an end to their reign of “kingmaking.”

- Consequences of Factional Politics: The relentless court factionalism had devastating repercussions for the empire:

- Assassinations: The political landscape was rife with violence, including regicide (murder of emperors) and assassination of powerful nobles, indicating a complete breakdown of law and order at the highest level.

- Bribery and Corruption: Positions, promotions, and jagirs were often secured through bribery and personal influence rather than merit. This fostered rampant corruption throughout the administration, eroding efficiency and public trust.

- Civil Wars: The struggle for the throne after Aurangzeb, and the subsequent internecine warfare between factions, diverted immense resources, manpower, and attention away from pressing state issues like defense, revenue collection, and maintaining order. These conflicts further destabilized the empire and weakened its military.

- Decline in Administrative Efficiency: The constant infighting meant that long-term strategic planning was impossible. Policies were inconsistent, and honest, capable administrators found it difficult to function. Revenue collection became erratic, justice was often subverted, and public works languished. The empire’s administrative machinery, once a marvel, ground to a halt.

In essence, court factionalism transformed the unified Mughal government into a battleground for competing interests. This internal fragmentation not only consumed the empire’s strength from within but also presented a clear opportunity for regional powers and foreign invaders to exploit its terminal weakness.

Crisis in the Mansabdari and Jagirdari Systems

The Mansabdari and Jagirdari systems were the twin pillars of Mughal administration, designed to ensure loyalty, military strength, and efficient revenue collection. The Mansabdars (holders of a “mansab” or rank) were assigned jagirs (revenue-yielding lands) in lieu of cash salaries to maintain troops and administer their assigned territories. While highly effective in its prime, this system began to crack under pressure, transforming from a source of strength into a significant cause of the empire’s internal decay.

- Structural Problems in the Mansabdari System:

- Mansabdar’s Dual Role: Each Mansabdar had a dual rank:

- Zat: Indicated the Mansabdar’s personal status and salary.

- Sawar: Indicated the number of cavalry he was expected to maintain. The system required Mansabdars to recruit, train, and maintain their assigned quota of troops, which were then available for imperial service. In return, they received revenue from their jagirs.

- The Intent vs. Reality: The system was designed to create a loyal military-administrative elite directly accountable to the emperor. However, several factors began to undermine its efficacy.

- Mansabdar’s Dual Role: Each Mansabdar had a dual rank:

- The Jagir Crisis: This was perhaps the most acute symptom of the system’s breakdown.

- Scarcity of Revenue-Yielding Jagirs:

- Continuous Wars: Decades of incessant warfare, particularly Aurangzeb’s prolonged campaigns in the Deccan, consumed vast resources and often resulted in the devastation of fertile lands. These devastated lands could not yield sufficient revenue, making them unattractive or unproductive as jagirs.

- Deccan Expansion: While ostensibly adding territory, many newly conquered Deccan lands were either arid, sparsely populated, or already under the sway of local Maratha chiefs who resisted Mughal authority. Assigning these lands as jagirs often meant assigning “paper” jagirs—lands that promised revenue but actually yielded very little or nothing. This increased the demand for productive jagirs in the core Mughal territories.

- Mismanagement and Corruption: Over time, mismanagement and corruption became endemic. Imperial officials often underreported the actual revenue potential of productive lands or diverted funds, further shrinking the pool of available profitable jagirs.

- Consequences of Jagir Scarcity:

- Increased Demand vs. Decreased Supply: The number of Mansabdars continued to grow, particularly after Aurangzeb, as new factions sought patronage and power. However, the number of readily available, revenue-generating jagirs dwindled rapidly. This created a severe imbalance.

- Long Waiting Periods: Mansabdars often faced long waiting periods to receive a profitable jagir. When they did receive one, they were often transferred frequently (paibaqi system), preventing them from developing a long-term interest in the land or its peasantry.

- “Be-Jagir” (Jagir-less) Mansabdars: Many Mansabdars remained “be-jagir” or were assigned unproductive jagirs, leading to resentment, discontent, and an inability to maintain their assigned contingent of troops. This directly weakened the military strength of the empire.

- Scarcity of Revenue-Yielding Jagirs:

- Extraction and Rural Distress:

- Pressure on Mansabdars: Faced with uncertain and insufficient income from their jagirs, Mansabdars, or more accurately, their agents (amils), resorted to desperate measures to maximize revenue from their assigned territories. They often ignored imperial regulations on revenue collection.

- Excessive Taxation: This pressure translated into excessive demands on the peasantry. Taxes were often arbitrary, collection methods coercive, and demands for land revenue (mal) and various cesses (abwabs) became unbearable.

- Rural Distress and Peasant Rebellions: The relentless exploitation led to widespread rural distress. Peasants, unable to meet the demands, abandoned their lands, fled, or resorted to rebellion. Movements like the Satnami revolt, Jat uprisings, and continued Maratha raids were fueled, in part, by this agrarian crisis. These rebellions further destabilized the countryside and reduced actual revenue collection.

- Falling Revenue for the State: The vicious cycle was complete: excessive extraction led to rural distress, which led to rebellions and abandoned lands, ultimately resulting in a significant decline in the actual revenue flowing into the imperial treasury, despite inflated land revenue figures on paper.

- Hereditary Mansabdars and Reduced Loyalty:

- Shift from Meritocracy: In the earlier, stronger phases of the empire, Mansabdars were appointed and promoted based on merit and performance, and their jagirs were transferable to prevent them from developing strong local roots and potentially challenging imperial authority.

- Decline in Loyalty: As central authority weakened, powerful nobles began to treat their Mansabs and jagirs as hereditary rights. They became increasingly entrenched in their regions, building personal armies and networks of patronage that superseded their loyalty to the distant and ineffective emperor.

- Rise of Independent Regional Powers: This transformation was crucial in the emergence of autonomous regional states. When a Mansabdar effectively became a hereditary ruler of a large territory (like the Nizam in Hyderabad or the Nawabs of Awadh and Bengal), their loyalty shifted from the emperor to their own nascent state. They withheld revenues, maintained their own armies, and pursued independent foreign policies, further fragmenting the empire.

The crisis in the Mansabdari and Jagirdari systems effectively crippled the Mughal Empire’s ability to maintain its military, collect revenue, and enforce its will across its vast territories. It turned its administrative backbone into a source of internal conflict, economic exploitation, and ultimately, disintegration.

The Burden of Over-centralization

The Mughal Empire, particularly in its zenith, operated on a highly centralized model. Power emanated from the emperor and his court in Delhi (or Agra), with an elaborate bureaucracy designed to implement imperial decrees across the vast realm. While this system worked well under strong, vigilant emperors who could effectively control their officials and swiftly address provincial issues, it became a significant liability as the empire expanded and its central leadership weakened. The Mughals, unlike many successful empires that adapted to a more decentralized or federal model for diverse and distant regions, largely maintained a rigid, top-down structure.

- Failure to Evolve a Federal Structure:

- Unitary Imperial Ideal: The Mughal ideal of governance was largely unitary, where all authority ultimately rested with the emperor. While there were provincial governors (Subahdars) and other officials, their powers were delegated from the center and theoretically revocable at will.

- Ignoring Regional Diversity: India is a subcontinent with immense linguistic, cultural, and administrative diversity. A highly centralized model struggled to effectively account for and manage the unique requirements and challenges of different regions, especially those geographically distant or culturally distinct from the heartland.

- No Delegation of Sovereign Powers: Unlike a federal system where constituent units (states or provinces) have defined spheres of sovereignty, Mughal provinces were merely administrative divisions, without inherent rights or powers. This meant that even minor decisions often had to be referred to the imperial court, leading to delays and inefficiencies.

- Concentration of Responsibilities in Delhi:

- The Emperor as the Sole Nexus: The emperor was not just the symbolic head but the actual source of all major authority. This meant:

- Appointments and Promotions: All significant appointments (Subahdars, Diwans, Mir Bakshis), promotions of Mansabdars, and grants of jagirs or titles required imperial sanction. This created a bottleneck at the court.

- Policy Formulation: Major policy decisions, military strategies, and even responses to local rebellions often awaited imperial directives.

- Judicial Appeals: The emperor was also the highest court of appeal, further burdening the central administration.

- Lack of Empowered Local Initiative: Provincial officials, even capable ones, often lacked the autonomy to make quick decisions or adapt policies to local conditions without imperial approval. This stifled local initiative and made the administration rigid and unresponsive.

- The “Darbar” Culture: The court (Darbar) became the epicenter of all activity. Nobles, petitioners, and provincial officials had to congregate there, leading to a constant drain on resources and time, and creating an environment ripe for bribery and influence peddling to gain the emperor’s ear.

- The Emperor as the Sole Nexus: The emperor was not just the symbolic head but the actual source of all major authority. This meant:

- Difficulty in Controlling Distant Provinces:

- Geographical Sprawl: The empire stretched from Kashmir to the Deccan, and from Bengal to Kabul. Provinces like Bengal, Assam, the Deccan, and even parts of Gujarat and Malwa were geographically distant from the imperial capital.

- Communication Delays: In an age before rapid communication, relaying orders, receiving reports, and dispatching troops or funds to distant provinces took weeks or even months. This created a significant lag between events on the ground and imperial response.

- Information Asymmetry: The central administration often relied on delayed and potentially manipulated reports from provincial officials, leading to an imperfect understanding of the real situation in distant areas.

- Opportunity for Autonomy: The combination of distance, communication delays, and weak emperors provided fertile ground for ambitious provincial governors to assert their independence. When the center was strong, swift punitive action could be taken against rebellious governors. But as the center weakened, these governors (like Murshid Quli Khan in Bengal, Saadat Khan in Awadh, and Nizam-ul-Mulk in Hyderabad) effectively transformed their provinces into autonomous states, merely paying nominal allegiance to the Mughal throne. They withheld revenue, maintained their own armies, and made independent treaties.

- Loss of Revenue and Resources: As provinces became autonomous, the imperial treasury lost vast sums of revenue that were formerly collected from these regions. This further crippled the central government’s ability to maintain its army and administration, creating a downward spiral.

In essence, the Mughal Empire’s over-centralized structure, which worked efficiently under strong personal rule, became an unmanageable burden when the personal qualities of the emperors declined. It created an inflexible system that could not adapt to its own growth or the changing political landscape, ultimately leading to fragmentation and the rise of independent regional powers.

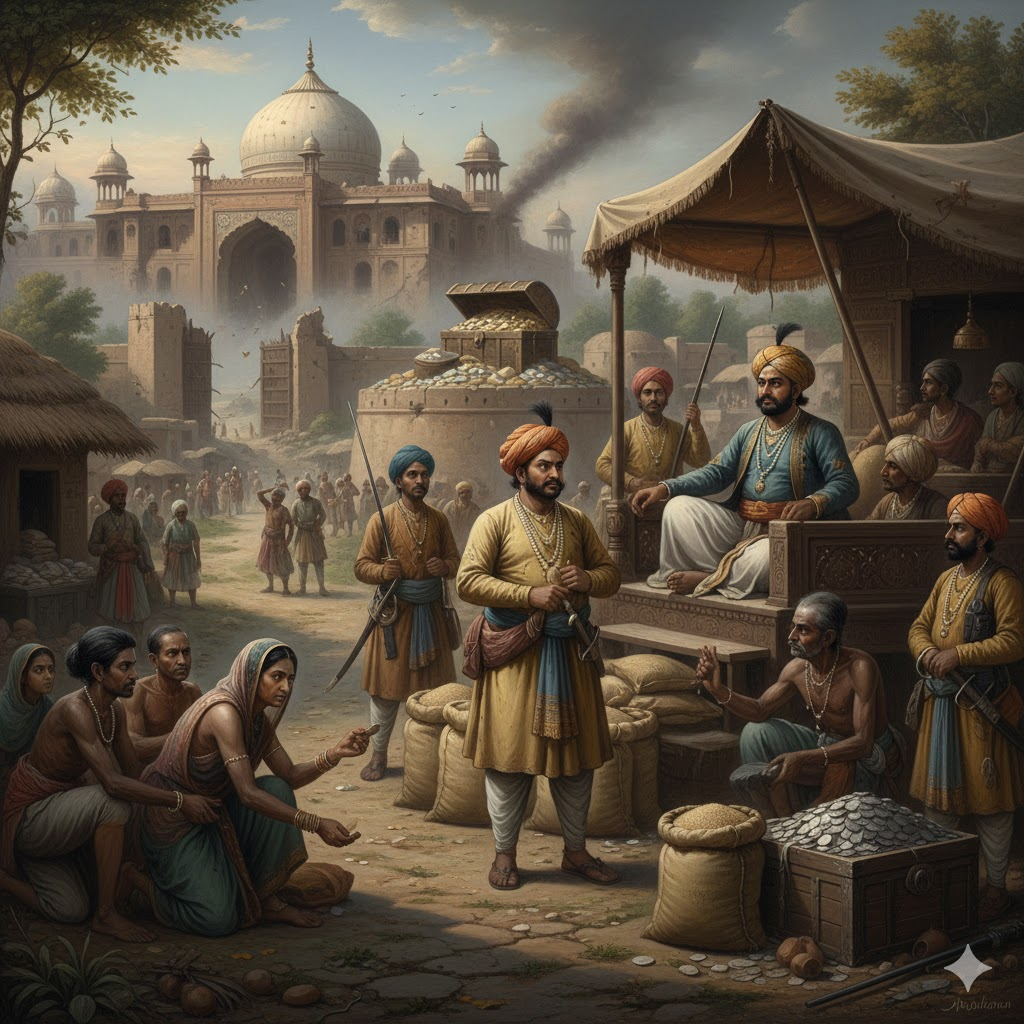

Corruption in Revenue Administration

The efficient collection and management of land revenue were the fiscal bedrock of the Mughal Empire. A sophisticated system was put in place to assess, collect, and transmit revenue to the imperial treasury. However, as central authority weakened and internal pressures mounted, this system became riddled with corruption, leading to a drastic reduction in state income, increased peasant suffering, and the empowerment of local intermediaries who increasingly defied imperial control.

- Exploitation by Officials:

- Amils: These were revenue collectors appointed by the imperial government or a Mansabdar in a jagir. Their primary duty was to assess and collect taxes from the peasantry. With lax central oversight, many Amils engaged in extortion, demanding more than the stipulated share from the peasants and pocketing the difference. They often falsified records, underreporting the actual collections to the state.

- Iqtadars: While the term “Iqta” refers to a pre-Mughal system, within the Mughal context, it broadly refers to the holders of revenue assignments (Jagirs). These Mansabdars, or their agents, were the de facto administrators of their assigned territories. Faced with the Jagir Crisis (scarcity of profitable jagirs and frequent transfers), they felt immense pressure to extract maximum revenue in the shortest possible time. This often meant ignoring the welfare of the peasants and resorting to oppressive taxation.

- Karoris: During Akbar’s time, Karoris were officials responsible for collecting revenue of one kror (ten million) dams. Over time, the term generally referred to local revenue officers. Like Amils, they were positioned to exploit their authority through illicit collections, bribes, and fudging accounts.

- Nexus of Corruption: These officials often formed a nexus with local moneylenders and powerful individuals, further entrenching the system of exploitation. Peasants were often forced to borrow at exorbitant rates to pay taxes, falling into a cycle of debt and bondage.

- Zamindars Become Semi-Independent:

- Original Role: Zamindars were hereditary landholders or local chieftains who often served as intermediaries between the state and the peasantry. They were recognized by the Mughals for their local influence and often assisted in revenue collection, for which they received a share.

- Exploitation of Weakness: As the central government’s grip weakened, Zamindars saw an opportunity to enhance their own power and wealth.

- They began to withhold revenue that was due to the imperial treasury, using it to build their personal fortunes, maintain private armies (retainers), and strengthen their local positions.

- They often carved out semi-independent domains, sometimes defying imperial authority outright, especially in regions distant from the capital or during periods of political turmoil.

- They too extracted additional cesses and taxes from the peasantry under their control, often for their own benefit, exacerbating rural distress.

- Challenge to Imperial Authority: The growing assertiveness and independence of Zamindars fundamentally undermined the imperial revenue system. The state lost direct control over vast tracts of land and the income derived from them, making it dependent on intermediaries who were increasingly unreliable and disloyal.

- Revenue Withheld from the Center:

- The Lifeline Severed: The most direct impact of this corruption and localized empowerment was the drastic reduction in the actual amount of revenue reaching the imperial treasury in Delhi.

- Financial Crisis: This directly contributed to a severe financial crisis. Without sufficient funds, the emperor could not:

- Pay the Mansabdars regularly, leading to further discontent and a decline in military effectiveness.

- Maintain the imperial army and construct public works.

- Respond effectively to rebellions or foreign invasions.

- Maintain the pomp and prestige of the imperial court, further diminishing its authority.

- Cycle of Decline: The inability to collect sufficient revenue meant a weaker army, which in turn meant less control over provinces and Zamindars, leading to even more withheld revenue—a vicious cycle that relentlessly pushed the empire towards insolvency.

- Corruption Grew Due to Weak Control:

- Lack of Oversight: A strong emperor and an efficient intelligence network were crucial for monitoring provincial and local officials. As emperors became weak and preoccupied with court intrigues, this oversight mechanism collapsed.

- Fading Fear of Punishment: The fear of imperial retribution, which once kept officials in check, diminished significantly. Corrupt practices became rampant because the likelihood of being caught and punished was low.

- Moral Decay: The general moral decay at the imperial court, with its own rampant factionalism and bribery, trickled down to all levels of administration. If the emperor and his closest advisors were seen to be corrupt or ineffective, there was little incentive for lower officials to remain honest or diligent.

Military Causes

Decay of the Once-Formidable Mughal Army

The Mughal Empire’s initial rise and expansion were largely due to its superior military organization, tactics, and technology, particularly its effective use of artillery and cavalry. However, by the 18th century, the Mughal military had become stagnant, failing to adapt to new advancements, while its command structure suffered from deep-seated inefficiencies and corruption. This made it increasingly vulnerable and ultimately incapable of protecting the empire.

- Outdated Military Technology:

- Reliance on Traditional Strengths: By the 18th century, the Mughal army still heavily relied on:

- Heavy Cavalry: Large contingents of horsemen, often heavily armored, were the primary striking force. While formidable in earlier centuries, their effectiveness was waning against disciplined infantry formations armed with firearms.

- War Elephants: Used for breaking enemy lines and as command platforms, elephants were increasingly a liability on the battlefield against modern artillery and musketry, becoming huge targets that could panic and rout their own forces.

- Traditional Artillery: While the Mughals were pioneers in using artillery in India, their cannons by the 18th century were often cumbersome, slow to reload, and lacked the mobility and precision of European field artillery.

- Lack of Disciplined Infantry: The Mughal infantry (paiks) was generally a poorly trained, ill-disciplined, and lightly armed force, often serving as camp followers or irregulars rather than a cohesive fighting unit. They lacked the rigorous drill, standardized weaponry, and tactical formations that characterized European infantry.

- Inadequate Naval Power: The Mughals largely neglected to develop a strong navy. Their focus remained on land-based expansion and control.

- Vulnerability to European Sea Power: This neglect left the Indian coastlines and lucrative maritime trade routes vulnerable to European trading companies (British, French, Dutch, Portuguese), who possessed superior naval technology and expertise.

- Control of Coastal Trade: European powers could easily blockade Indian ports, control coastal trade, and land troops unchallenged, giving them a significant strategic advantage that the Mughals simply could not counter. This was crucial for the British in establishing their economic and later political dominance.

- In Contrast: European Military Superiority: The European trading companies, particularly the British and French, benefited from the military revolution ongoing in Europe. They employed:

- Muskets and Flintlock Guns: Standardized, relatively rapid-firing muskets (flintlocks) put lethal firepower in the hands of disciplined infantry.

- Modern Artillery Brigades: Lightweight, highly mobile, and accurate field artillery that could be rapidly deployed and reloaded, devastating traditional Mughal formations.

- Disciplined Infantry Drills: European armies emphasized rigorous training, marching in tight formations, volley fire, and bayonet charges, which were devastating against the more loosely organized Mughal forces. They could form squares to repel cavalry and deliver sustained firepower.

- Professionalization: European companies hired and trained native sepoys (Indian soldiers) under European officers, instilling discipline and modern tactics, creating an army far superior to regional Indian forces.

- Reliance on Traditional Strengths: By the 18th century, the Mughal army still heavily relied on:

- Weakness in Command and Organization:

- Appointment based on Nobility, Not Merit: The Mansabdari system, which linked rank to military command, had degenerated. High commands were often given to nobles based on their aristocratic lineage, factional allegiance, or personal influence at court, rather than proven military competence or tactical genius. This meant that crucial battles were often led by inexperienced or ineffective generals.

- Armies of Nobles Acted Independently: The imperial army was not a unified, centrally controlled force. Instead, it was a conglomeration of contingents supplied by various Mansabdars. These contingents often owed primary loyalty to their respective noble (Jagirdar) rather than the emperor.

- Lack of Coordination: This led to a severe lack of coordination on the battlefield, with different contingents fighting for their own immediate interests or withdrawing if their patron was threatened.

- Internal Rivalries: Factional rivalries among nobles often played out on the battlefield, undermining overall strategic objectives.

- Dispersed Resources: The practice of nobles maintaining their own armies meant that the emperor did not have a large, standing, professional imperial army directly under his command, capable of rapid deployment or sustained campaigns.

- Lack of Military Modernization: There was a systemic resistance to adopting new military technologies and tactics. The Mughal court was often too engrossed in internal politics and too complacent in its former glory to recognize the existential threat posed by European military advancements. They saw European soldiers as mere mercenaries or traders, not as a military paradigm shift.

- Financial Constraints: The financial crisis further hampered any efforts at modernization. There were simply insufficient funds to invest in new weapons, training, or a modern navy.

- Intellectual Stagnation: The Mughal military intellectual tradition became stagnant, failing to innovate or learn from the changing global military landscape.

Economic Causes

The Financial Collapse of a Once-Wealthy Empire

The Mughal Empire, famed for its opulence and vast wealth, faced a severe and irreversible economic crisis in its later stages. This crisis was a complex interplay of depletion of resources, declining productivity, and a disruption of trade, all exacerbated by political instability and military overextension.

- Depletion of Treasury:

- Aurangzeb’s Deccan Wars (1681–1707): This was perhaps the single most significant factor in draining the imperial treasury. Aurangzeb spent nearly 27 years (the last two decades of his life) in the Deccan, attempting to suppress the Marathas and annex the Shia Deccan Sultanates (Bijapur and Golconda).

- Massive Troop Expenditure: Maintaining a huge imperial army far from the capital for decades, constantly engaging in warfare, involved enormous costs. Salaries, supplies, logistics, and equipment for hundreds of thousands of soldiers and their camp followers drained the treasury dry.

- Loss of Lives and Resources: The continuous warfare led to massive casualties on both sides and the devastation of vast tracts of land in the Deccan. This not only reduced the potential for future revenue but also resulted in a loss of skilled manpower.

- Provinces Left Devastated: The Deccan region, once a source of wealth, became a perpetual battlefield. Agriculture and trade were disrupted, leading to widespread famine and depopulation in many areas. Even other provinces suffered as resources were constantly diverted to the Deccan.

- Never Recovered: The financial strain of the Deccan campaigns was so immense that the imperial treasury never truly recovered. Subsequent emperors inherited a depleted coffer, making it impossible to invest in infrastructure, maintain a strong army, or even pay officials regularly.

- Nadir Shah’s Invasion (1739): The sack of Delhi by Nadir Shah of Persia delivered the final, crippling blow to the imperial finances. He carried away an estimated 70 crores of rupees in wealth, including the fabled Peacock Throne and the Koh-i-Noor diamond. This theft of immense liquid assets and symbols of power meant that the Mughals lost any hope of financial rejuvenation.

- Aurangzeb’s Deccan Wars (1681–1707): This was perhaps the single most significant factor in draining the imperial treasury. Aurangzeb spent nearly 27 years (the last two decades of his life) in the Deccan, attempting to suppress the Marathas and annex the Shia Deccan Sultanates (Bijapur and Golconda).

- Decline in Agricultural Productivity:

- Over-assessment of Land: To compensate for dwindling revenues and fund wars, the state, and later the Mansabdars, began to demand higher and often unrealistic land revenue. The official assessment (jama) often far exceeded the actual yield (hasil).

- Excessive Tax Collection: Coupled with over-assessment, the actual collection methods became increasingly coercive. Amils and Jagirdars, under pressure to extract maximum revenue, often ignored regulations and demanded arbitrary taxes and cesses.

- Natural Calamities: India was prone to natural disasters like droughts and floods. A strong government would offer relief and support for recovery; a weak, corrupt administration could not or would not, further exacerbating peasant distress.

- Peasant Flight: Faced with unbearable taxes, exploitation, and the destruction caused by wars and famine, peasants often abandoned their fields and villages. This “peasant flight” further reduced the land under cultivation and, consequently, the taxable base of the empire. Fleeing peasants either joined rebellious groups or sought refuge in forests or other regions, disrupting the rural economy.

- Zamindar Exploitation: As discussed earlier, Zamindars, acting as intermediaries, often engaged in their own forms of exploitation, adding another layer of burden on the peasantry and diverting revenue that should have gone to the state.

- Reduced Taxable Base: The combined effect of these factors was a significant and continuous decline in agricultural output and the actual revenue that could be collected. This meant less money for the imperial treasury, a weaker state, and a more impoverished rural population.

- Decline of Trade and Industries:

- Insecurity on Roads due to Rebellions: The widespread political instability, peasant uprisings, and the rise of autonomous regional powers (Marathas, Jats, Sikhs, Pindaris) led to a breakdown of law and order. Major trade routes became unsafe due to banditry and local levies imposed by various warring factions. This increased the cost of transportation, discouraged merchants, and disrupted the flow of goods.

- Fall in Demand for Indian Textiles as Europeans Competed: While initially, European demand for Indian textiles boosted certain industries, the later phase saw European companies (especially the British) begin to control production and eventually promote their own manufactured goods. This was a more long-term effect, but the decline in demand for traditionally woven Indian goods, and the imposition of restrictive trade policies by European powers, began to impact indigenous industries.

- Disruption of Guilds in War Zones: Many specialized artisanal guilds and industrial centers were located in areas frequently affected by warfare. Constant conflict, destruction of towns, and displacement of skilled laborers disrupted traditional industries like textile weaving, metalwork, and handicrafts. The infrastructure supporting these industries was destroyed, and artisans often lost their patronage.

- Lack of Imperial Patronage: With the imperial treasury depleted and the court focused on survival, patronage for arts, crafts, and luxury goods (which had previously driven much of the urban economy) significantly declined.

Social & Religious Causes

The Seeds of Discord Sown by Religious Policies

The social fabric of the Mughal Empire was diverse, encompassing various religious and ethnic groups. Earlier emperors like Akbar fostered a policy of religious tolerance and inclusion, integrating different communities into the state. However, Aurangzeb’s shift towards greater religious orthodoxy reversed these policies, creating deep resentment and fueling long-term resistance from non-Muslim communities, ultimately contributing to the empire’s internal fragmentation and decline.

- Religious Orthodoxy of Aurangzeb: Aurangzeb, a devout Sunni Muslim, sincerely believed in governing according to orthodox Islamic principles. While his intentions might have been to purify the state and gain the support of the Sunni Ulema, his policies had severe political repercussions.

- Reimposition of Jizya (Tax on Non-Muslims):

- Symbolic and Financial Burden: Abolished by Akbar, the jizya was a poll tax levied on non-Muslims. Its reimposition in 1679 was highly symbolic, signaling a reversal of the inclusive policies of his predecessors and reinforcing the idea of a religiously discriminatory state.

- Widespread Resentment: While the actual financial burden might have varied, the symbolic insult and the practical difficulties of collection (often involving humiliation) caused widespread resentment among the Hindu majority across the empire. It fostered a sense of being second-class citizens.

- Destruction of Temples in Some Regions:

- Context of Rebellion: While often presented as a blanket policy, temple destruction under Aurangzeb was frequently linked to acts of rebellion or perceived defiance by local Hindu rulers or communities. However, the destruction of prominent temples, such as the Kashi Vishwanath Temple at Varanasi and the Kesava Deva Temple at Mathura, was deeply offensive to Hindu sentiments and served as powerful symbols of imperial oppression.

- Loss of Goodwill: These actions irrevocably damaged the goodwill and trust that earlier emperors had built with the Hindu population and their religious leaders.

- Enforced Sharia Laws and Other Restrictive Measures:

- Moral Policing: Aurangzeb sought to enforce Sharia law more strictly, which included banning practices deemed un-Islamic, such as public music, dancing, and drinking alcohol at court. He also discontinued the practice of darshan (public appearance of the emperor) and phased out the celebration of the Persian festival of Nauroz.

- Economic Restrictions: Certain economic activities, like imposing higher customs duties on Hindu merchants compared to Muslim merchants, further fueled resentment.

- Alienation of Courtiers: The austere atmosphere at court and the moral policing alienated many nobles, including some Muslims, who preferred the more liberal and culturally vibrant atmosphere of previous reigns.

- Reversed Akbar’s Syncretic Policies (Sulh-i-Kul):

- From Inclusion to Exclusion: Akbar’s policy of “Sulh-i-Kul” (universal peace) promoted religious tolerance, interfaith dialogue, and the inclusion of diverse groups into the state apparatus regardless of religion. Aurangzeb’s policies represented a dramatic shift away from this inclusive model towards a more exclusive, religiously defined state.

- Disintegration of Social Cohesion: This reversal directly undermined the social cohesion and political stability that Akbar had painstakingly built, leading to fragmentation along religious lines and inspiring resistance movements.

- Reimposition of Jizya (Tax on Non-Muslims):

- Alienation and Resulting Rebellions: Aurangzeb’s religious policies directly contributed to the alienation of several key communities, transforming simmering discontent into open rebellion and full-scale warfare.

- Rajputs → Rebellion:

- Breakdown of Alliance: The Rajputs, particularly the Rathors of Marwar and the Sisodias of Mewar, had been staunch allies and pillars of the Mughal Empire since Akbar’s time. Aurangzeb’s attempts to interfere in Marwari succession disputes, his military annexation of Jodhpur, and the reimposition of jizya deeply offended them.

- Prolonged Conflict: This led to a prolonged and costly Rajput rebellion, particularly in Marwar and Mewar (1679-1707). While the Mughals eventually achieved a partial settlement, the alliance was irrevocably broken. The Rajputs, once loyal military commanders and administrators, became alienated, no longer providing the same unwavering support or contributing to the imperial cause with the same vigor. Their absence weakened the imperial military and created persistent unrest in a crucial region.

- Marathas → Full-scale War:

- Existing Resistance: The Marathas under Shivaji had already begun their resistance in the Deccan before Aurangzeb’s full Deccan campaign. However, Aurangzeb’s relentless and religiously tinged pursuit of them, combined with his annexation of the Deccan Sultanates, transformed a regional uprising into a full-scale, protracted war of attrition.

- Hindu Identity: Shivaji cleverly utilized the religious aspect to rally Hindu support, portraying his struggle as a defense of Dharma against Mughal oppression. Aurangzeb’s policies inadvertently strengthened this narrative.

- Drained Resources: The Maratha war drained the Mughal treasury, exhausted its military resources, and kept Aurangzeb away from the central administration for decades, leaving the core empire vulnerable. The Marathas, masters of guerrilla warfare, were never decisively defeated and emerged as a major power in the 18th century, directly contributing to the empire’s downfall.

- Sikhs → Militarization under Guru Gobind Singh:

- From Pacifism to Militancy: The Sikhs, initially a peaceful spiritual community, began to transform into a militant political-military force in response to Mughal persecution. The execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur by Aurangzeb for refusing to convert to Islam was a turning point.

- Formation of the Khalsa: His son, Guru Gobind Singh, in 1699, formally inaugurated the Khalsa, a brotherhood of warrior-saints, giving the Sikh community a distinct military and political identity.

- Persistent Challenge: The Sikhs became a persistent challenge to Mughal authority in Punjab, tying up imperial resources and contributing to the instability in the northwestern frontier region. They would emerge as a formidable regional power in the 18th century under leaders like Banda Bahadur and later the Sikh Misls.

- Rajputs → Rebellion:

Social & Religious Causes (Continued): Strengthening of Caste & Local Identities and Failure of Integration

While earlier Mughal emperors, particularly Akbar, made concerted efforts to integrate diverse social groups into a broader imperial identity through policies of tolerance and shared patronage, these efforts waned under later rulers, especially Aurangzeb. As the central authority weakened, local, caste-based, and regional identities reasserted themselves, often coalescing into potent resistance movements that challenged and ultimately undermined the overarching Mughal state. The failure to evolve a truly inclusive national identity for the vast and diverse Indian subcontinent proved to be a fatal flaw.

- Failure to Integrate Various Social Groups:

- “Mughal Identity” as Elite: The “Mughal identity” largely remained an elite phenomenon, associated with the court, the Mansabdari system, and the urban centers. It rarely permeated deeply into the vast rural populace, especially beyond the core regions of the empire.

- Limited Social Mobility: While the Mansabdari system offered some upward mobility, for the vast majority, social structures remained highly traditional and localized, often rooted in caste, clan, or tribal affiliations.

- Withdrawal of Imperial Patronage: As the empire declined, imperial patronage for local elites, religious institutions, and cultural activities diminished. This meant local leaders had less incentive to align with the empire and more reason to cultivate their own regional power bases.

- Cultural Chasm: Despite centuries of rule, a fundamental cultural and political chasm often remained between the imperial Persianate/Turkic elite and the diverse indigenous populations, particularly in distant regions or those with strong pre-existing traditions.

- Identity-Based Regional Resistance: The decline of central authority, coupled with policies that alienated communities (especially Aurangzeb’s), provided fertile ground for these local and identity-based groups to organize and launch revolts, gradually chipping away at the empire’s territory and legitimacy. These were not merely economic or political revolts; they often carried a strong cultural or religious identity.

- Sikh Identity → Khalsa:

- Religious Persecution: As discussed, the Mughal persecution of Sikh Gurus (Guru Arjan Dev and Guru Tegh Bahadur) and the imposition of jizya deeply offended the Sikh community in Punjab.

- Militarized Identity: Under Guru Gobind Singh, the Sikh identity was consciously forged into a distinct warrior brotherhood—the Khalsa. This transformation moved beyond mere religious belief to encompass a socio-political-military organization dedicated to defending its faith and community.

- Assertion of Sovereignty: The Khalsa’s armed resistance, first under Guru Gobind Singh and then under Banda Bahadur, directly challenged Mughal rule in Punjab, eventually leading to the formation of independent Sikh principalities (Misls) that effectively ended Mughal control over the region.

- Maratha Identity → Swarajya:

- Regional Pride and Nationalism: The Marathas, under Shivaji, consciously articulated a strong regional identity rooted in Marathi language, culture, and a sense of defending their homeland (Maharashtra) against an external (Mughal) power. Shivaji’s concept of Swarajya (self-rule or own kingdom) was a powerful rallying cry that resonated deeply with the local populace.

- Guerilla Warfare: Their distinctive military tactics, combined with their strong local ties and popular support, made them incredibly difficult for the Mughals to defeat.

- Pan-Indian Ambition: After Shivaji, and particularly under the Peshwas, the Maratha confederacy expanded its influence across much of India, challenging Mughal power directly and extracting revenue (Chauth and Sardeshmukhi) from Mughal territories. They became a formidable contender for imperial power themselves, even sacking Delhi on occasion.

- Jats → Agrarian Revolt:

- Local Peasant Identity: The Jats were a powerful community of agrarian peasants and pastoralists predominantly found in the Agra-Delhi region. Their revolts, starting in the late 17th century, were initially driven by agrarian grievances (excessive taxation, oppression by local officials and Zamindars) and local clan loyalties.

- Community and Caste Solidarity: These revolts quickly took on an identity-based character, with Jat leaders like Gokula, Raja Ram, and Churaman rallying their kinsmen and caste fellows. They challenged Mughal authority by plundering imperial lines of communication and towns and establishing their own local chieftains.

- Formation of Bharatpur State: Their persistent rebellion eventually led to the establishment of the independent Jat state of Bharatpur, right on the doorstep of the Mughal capital, a powerful symbol of the empire’s inability to control its immediate hinterland.

- Rajputs → Assertion of Autonomy:

- Warrior Clan Identity: The Rajputs had a strong, ancient warrior identity rooted in their clan lineages and kingdoms. While they had initially forged alliances with the Mughals (especially under Akbar), this was always a relationship of semi-autonomous states.

- Reaction to Overreach: Aurangzeb’s interference in their internal affairs (Marwar succession) and his religious policies were perceived as a direct affront to their honor and autonomy.

- Reassertion of Independence: When the central Mughal power weakened, the major Rajput states, such as Jaipur (under Sawai Jai Singh) and Jodhpur, largely asserted their complete independence, often expanding their territories and forging alliances among themselves, effectively withdrawing their crucial military and administrative support from the empire.

- Sikh Identity → Khalsa:

You’ve outlined the Emergence of Regional Powers perfectly, identifying the three distinct types of states that rose from the ashes of Mughal decline. This fragmentation of political power was a direct and devastating consequence of the internal weaknesses we’ve been discussing, and it fundamentally altered the political map of India, setting the stage for European dominance.

Emergence of Regional Powers: The Fragmentation of the Mughal Empire

The most visible and immediate consequence of the internal decay of the Mughal Empire was the rise of numerous independent and semi-independent regional states. As the central authority in Delhi weakened, emperors became mere figureheads, and the ambitious and capable provincial governors, as well as rebellious indigenous groups, seized the opportunity to carve out their own domains. This created a highly fragmented and competitive political landscape across the Indian subcontinent.

- Successor States (Old Mughal Provinces): These were provinces of the Mughal Empire where governors (Subahdars or Diwans), originally appointed by the emperor, gradually became de facto independent rulers. They often maintained a nominal allegiance to the Mughal emperor, issuing coins in his name and seeking his firman (royal decree) for legitimacy, but in practice, they controlled all aspects of governance within their territories. Their autonomy stemmed from their strong local power bases and the central government’s inability to enforce its will.

- Awadh (Oudh) (Saadat Khan Burhan-ul-Mulk, 1722):

- Founder: Saadat Khan, a Persian adventurer, was appointed governor of Awadh in 1722. He quickly suppressed local Zamindars, streamlined the revenue system, and built a loyal army.

- Autonomy: While nominally subordinate to Delhi, Awadh became effectively independent under his and his successors’ rule (Safdar Jang, Shuja-ud-Daula). They managed their own finances, justice, and military, transforming the governorship into a hereditary nawabship.

- Strategic Importance: Located strategically between Delhi and Bengal, Awadh became a significant power center, often influencing North Indian politics.

- Hyderabad (Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah I, 1724):

- Founder: Mir Qamar-ud-din Siddiqi, a powerful Turani noble and one of Aurangzeb’s most capable generals, was appointed Subahdar of the Deccan in 1724. He was granted the title Nizam-ul-Mulk.

- Consolidation: Frustrated by the factionalism at the Mughal court, he retreated to the Deccan, suppressed the Marathas locally (at least initially), streamlined administration, and established the Asaf Jahi dynasty.

- Key Power: Hyderabad emerged as a major independent state in the South, controlling vast territories and wielding significant influence, though it too would eventually become entangled in Anglo-French rivalries.

- Bengal (Murshid Quli Khan, 1717):

- Founder: Murshid Quli Khan, originally appointed Diwan of Bengal by Aurangzeb, effectively took control of the province in 1717. He proved to be a shrewd administrator, reorganizing the revenue system (malzamini system) and bringing stability to Bengal.

- Hereditary Rule: He transferred the capital to Murshidabad and made his position virtually hereditary, passing it on to his son-in-law, Shuja-ud-Din, and then to Alivardi Khan.

- Economic Prosperity (initial): Despite its political separation, Bengal initially thrived economically under these Nawabs, attracting European trade. However, its wealth eventually made it a prime target for European powers, leading to the Battle of Plassey (1757) and the eventual British takeover.

- Awadh (Oudh) (Saadat Khan Burhan-ul-Mulk, 1722):

- Rebel States: These states emerged from direct rebellion against Mughal authority, often fueled by economic grievances, religious persecution, or a strong sense of community/regional identity. They actively challenged and often defeated Mughal armies, establishing their own independent polities.

- Marathas (Peshwas at Pune):

- Origin: Emerging from the Deccan under Shivaji in the late 17th century, the Marathas were fiercely independent and grew into the most formidable indigenous power in the 18th century.

- Peshwa Dominance: After Shivaji’s successors, real power shifted to the Chitpavan Brahmin Peshwas based at Pune (Balaji Vishwanath, Baji Rao I, Balaji Baji Rao).

- Confederacy: The Maratha Empire evolved into a confederacy of powerful chiefs (Scindias, Holkars, Gaekwads, Bhonsles) under the nominal leadership of the Peshwa. They expanded dramatically, raiding and collecting Chauth and Sardeshmukhi from vast areas of Mughal territory, fundamentally destabilizing the empire.

- Sikhs (Misls, later under Ranjit Singh):

- Militarization: As discussed, Mughal persecution led to the militarization of the Sikh community under Guru Gobind Singh and Banda Bahadur.

- Misls: After Banda Bahadur’s death, the Sikh community organized into twelve autonomous confederacies known as Misls. These Misls controlled large parts of Punjab.

- Consolidation under Ranjit Singh: In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Maharaja Ranjit Singh consolidated these Misls into a powerful Sikh Empire, becoming a major regional power in northwestern India.

- Jats (Bharatpur State):

- Agrarian Uprising: The Jats, a community of agrarian people around Delhi and Agra, revolted against Mughal oppression and excessive land revenue demands, asserting their local identity.

- Founding of Bharatpur: Under leaders like Churaman and Badan Singh, they established the independent state of Bharatpur in the early 18th century, a powerful symbol of Mughal weakness in its own heartland.

- Satnamis: A sect of Hindu ascetics and peasants who launched a fierce but short-lived rebellion in the Haryana region against Mughal authority under Aurangzeb. Though suppressed, it highlighted the deep-seated rural unrest.

- Afghans (Rohillas):

- Rohilkhand: Various Afghan tribes, notably the Rohillas, established an independent principality called Rohilkhand in the fertile region of Katehar (modern-day western Uttar Pradesh) after the decline of Mughal authority. They became a significant local power, often clashing with Awadh and the Marathas.

- Marathas (Peshwas at Pune):

- Independent Kingdoms: These were older, pre-existing kingdoms that had either been partially subjugated by the Mughals or maintained a degree of autonomy, and fully reasserted their independence as Mughal power waned.

- Rajputana States:

- Loss of Imperial Control: After Aurangzeb’s aggressive policies alienated them, Rajput states like Marwar (Jodhpur), Mewar (Udaipur), and Amber (Jaipur) effectively became independent.

- Regional Dominance: They often expanded their territories, formed their own alliances, and dominated the politics of Rajasthan, no longer contributing to the imperial cause.

- Travancore:

- Southern Independence: In the far south, states like Travancore in Kerala emerged as powerful and independent kingdoms. Under rulers like Marthanda Varma (1729-1758), Travancore built a formidable army, defeated the Dutch, and expanded its territory, maintaining its independence from both Mughal and later European dominance for a significant period.

- Mysore:

- Wodeyar Dynasty: The Wodeyar dynasty had ruled Mysore for centuries. As Mughal control weakened, their state flourished.

- Rise of Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan: In the mid-18th century, Hyder Ali, a brilliant military commander, usurped power and, along with his son Tipu Sultan, transformed Mysore into a formidable military and economic power, directly challenging British expansion in the South.

- Rajputana States:

Foreign Invasions That Shattered the Empire

While internal decay was steadily weakening the Mughal Empire, two major foreign invasions in the 18th century acted as powerful external shocks, accelerating its decline and demonstrating its terminal weakness to the world. These invasions drained its last reserves of wealth, destroyed its prestige, and further exposed its vulnerability.

- Nadir Shah’s Invasion (1739): The Persian Cataclysm Nadir Shah, the ambitious and ruthless ruler of Persia (Iran), observed the growing weakness and internal disarray of the Mughal Empire. He saw an opportunity to enrich his treasury and enhance his empire’s prestige.

- Reasons for Invasion:

- The Mughal failure to check Afghan rebels along the border, who then fled into Mughal territory.

- Nadir Shah’s ambition for conquest and wealth, knowing India’s legendary riches.

- The clear signals of Mughal military and political decline.

- Battle of Karnal (1739): This was the decisive engagement. Nadir Shah’s well-drilled army, though smaller, was more cohesive and militarily superior to the disorganized and faction-ridden Mughal forces under Emperor Muhammad Shah ‘Rangeela’. The Mughal army was decisively defeated within hours. Key Mughal nobles like Saadat Khan (Nawab of Awadh) and Khan-i-Dauran were killed or captured.

- Sack of Delhi: Following the victory, Nadir Shah marched into Delhi. Initially, he exercised restraint, but a riot by some Delhi citizens against his soldiers provoked a brutal massacre. For several weeks, Delhi was subjected to plunder and destruction.

- Immeasurable Wealth Looted: The city was systematically stripped of its treasures. The estimated value of the loot is staggering, often cited in the tens of crores of rupees (trillions in today’s value, though exact comparisons are difficult).

- Symbols of Power Seized: Among the most famous items taken were the legendary Peacock Throne (Takht-i-Taus), a symbol of Mughal imperial grandeur, and the fabled Koh-i-Noor diamond, then the largest known diamond in the world.

- Impact of Nadir Shah’s Invasion:

- Mughal Prestige Destroyed: The sack of Delhi and the emperor’s humiliation shattered whatever remaining prestige and moral authority the Mughal dynasty held. It proved that the ‘great’ Mughal Empire could be easily defeated and plundered by a foreign power.

- Treasury Emptied: The enormous wealth carried away by Nadir Shah was an irreversible blow to the already depleted imperial finances. This meant the Mughals had no resources to fund their army, pay their officials, or recover from their internal crises.

- Northwest Frontier Exposed: The invasion completely exposed the vulnerability of the Mughal’s northwestern frontier. It demonstrated that the traditional defenses were ineffective and left a vacuum that future invaders would exploit. The invasion itself removed any illusion of security in India.

- Further Fragmentation: The spectacle of Mughal weakness emboldened provincial governors and regional powers to assert even greater independence, accelerating the disintegration of the empire.

- Reasons for Invasion:

- Ahmad Shah Abdali (1748–1767): The Afghan Scourge Ahmad Shah Abdali (or Durrani) was Nadir Shah’s most capable general. After Nadir Shah’s assassination in 1747, Abdali carved out his own Afghan empire. Having seen the riches of India and the weakness of the Mughals firsthand, he followed Nadir Shah’s path.

- Motivations: To establish Afghan supremacy, to secure wealth, and to lead a holy war (jihad) against the Marathas and Sikhs, whom he viewed as infidels.

- Seven Invasions: Between 1748 and 1767, Abdali launched seven major invasions into India, primarily targeting the vulnerable Punjab and Delhi regions. Each invasion was devastating.

- Major Impacts:

- Punjab Frequently Ravaged: The Punjab region, strategically vital as the gateway to India, became a constant battlefield. Abdali repeatedly sacked Lahore and other cities, weakening Mughal and Sikh control, disrupting trade, and causing immense suffering. This constant instability prevented any single power from consolidating control over Punjab for decades.

- Marathas Weakened in Third Battle of Panipat (1761): This was Abdali’s most significant achievement in India. The Marathas, who by this time had become the dominant indigenous power and were marching towards Delhi with ambitions of establishing their own empire, posed the main challenge to Abdali’s control over Punjab. The two powers clashed at the Third Battle of Panipat in January 1761.

- Decisive Defeat: The Marathas suffered a catastrophic defeat, losing tens of thousands of soldiers and many of their most important military commanders and the Peshwa’s cousin.

- End of Maratha Imperial Ambitions: While Abdali himself could not consolidate his gains in India and eventually returned to Afghanistan, the Battle of Panipat dealt a mortal blow to the Marathas’ pan-Indian imperial ambitions. It shattered their military prestige and created a power vacuum in North India.

- Benefit to British: Critically, this battle weakened the two most formidable indigenous powers (Mughals were already defunct, Marathas now devastated), creating a political vacuum that the British East India Company was perfectly poised to exploit. It removed the last major obstacle to British expansion in North India.

- Mughal Territory Drastically Reduced: By the end of Abdali’s invasions, the Mughal Empire had shrunk to a small enclave around Delhi. The emperor was a puppet, stripped of territory, wealth, and real power, existing only by the grace of whichever regional power or invader was currently dominating Delhi.

Rise of European Powers: The Final Blow and the Dawn of Colonialism

While the Mughal Empire was crumbling from within and battered by foreign invaders, a new, technologically superior, and politically astute force was rising on the Indian subcontinent: the European trading companies. Initially focused on trade, the British and French East India Companies gradually transformed into political and military powers, exploiting the prevailing chaos and using their distinct advantages to establish dominance, ultimately leading to the formal end of the Mughal Empire and the beginning of colonial rule.

- Military Superiority: The European companies possessed distinct military advantages that Indian powers, including the Mughals, failed to adequately counter or adopt.

- Disciplined Infantry: European armies, whether company troops or their sepoy recruits, were rigorously trained in modern drills, marching in tight formations, and executing synchronized volley fire. This disciplined infantry, armed with flintlock muskets and bayonets, could hold its ground against overwhelming numbers of traditional Indian cavalry and infantry.

- Strong Artillery: European field artillery was lighter, more mobile, and more accurate than the heavier, slower Mughal cannons. They could deliver devastating firepower on the battlefield, disrupting enemy formations and causing heavy casualties.

- Naval Dominance: The European powers, especially the British, had absolute command of the seas. This allowed them to:

- Control maritime trade routes, crippling Indian commerce and securing their own supply lines.

- Transport troops and supplies efficiently around the Indian coastline.

- Project power onto coastal regions and launch amphibious operations, which Indian states could not counter.

- This naval supremacy was a strategic advantage that the land-focused Mughals and other Indian powers never developed.

- Mercenary Recruitment & Training: The European companies effectively recruited and trained large numbers of Indian sepoys. These sepoys, disciplined by European officers and equipped with modern weapons, proved to be far more effective than the irregularly paid and poorly trained soldiers of many Indian rulers. This meant the Europeans could field large, modern armies even with relatively small numbers of their own European troops.

- Political Manipulation and Exploitation of Indian Weaknesses: The European companies were not just militarily strong; they were also masters of political intrigue, leveraging the fragmented Indian political landscape to their advantage.

- Support for Rival Indian Princes: The British and French skillfully played off rival Indian princes and factions against each other. They would support one claimant to a throne against another, or ally with one state against its enemy, demanding territorial or commercial concessions in return. This strategy, often called “divide and rule,” allowed them to gain influence, territory, and revenue without directly engaging all Indian powers simultaneously.

- Battle of Plassey (1757): The Turning Point in Bengal:

- Conspiracy: This battle was less a military victory and more a result of a deep-seated conspiracy orchestrated by the British East India Company (EIC) under Robert Clive.

- Betrayal of Mir Jafar: Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, faced a mutiny within his own army led by his commander-in-chief, Mir Jafar, who had been bribed by Clive. During the battle, Mir Jafar’s large contingent remained inactive.

- Consequences: The EIC decisively defeated the Nawab’s forces. Mir Jafar was installed as a puppet Nawab, and the EIC gained immense power and financial control over Bengal, a rich province. This marked the beginning of direct British territorial rule in India. It demonstrated how internal treachery, coupled with European military prowess, could easily topple an Indian ruler.

- Battle of Buxar (1764): The Mughal Emperor’s Humiliation:

- Alliance Against British: This battle was a far more significant military engagement than Plassey. It pitted the forces of the British East India Company against a grand alliance of the deposed Nawab of Bengal (Mir Qasim), the Nawab of Awadh (Shuja-ud-Daula), and critically, the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II himself.

- Decisive British Victory: The British EIC, under Major Hector Munro, decisively defeated this combined Indian force. This victory was a clear demonstration of British military supremacy over the most significant Indian powers of the time, including the nominal head of the Mughal Empire.

- Diwani Rights to EIC: The subsequent Treaty of Allahabad (1765) was catastrophic for the Mughal Empire. Emperor Shah Alam II was forced to issue the Diwani (rights to collect revenue) of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa to the British East India Company. This effectively made the EIC the paramount financial authority over these vast and rich provinces, while the Emperor retained only nominal administrative (Nizamat) control, which too was soon usurped.

- Mughal Emperor Becomes a Pensioner: After 1764, the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II became a mere pensioner of the British East India Company, living on an allowance provided by them. He lost all real political and financial power, and the symbolic head of the once-great Mughal Empire became a tool in the hands of a foreign trading company. This event officially ended any pretense of Mughal sovereignty and established the EIC as a major political power in India.

Stages of Mughal Decline

| Stage / Period | Key Features | Major Developments |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 1707–1740 Internal Weakness | • Weak successors after Aurangzeb • Intense court factions • Jagirdari crisis • Administrative decay | • Rise of Sayyid Brothers • Frequent rebellions (Jats, Sikhs, Rajputs) • Provinces drift toward autonomy |

| Stage 2 1740–1761 External Shocks | • Foreign invasions • Military defeats • Decline in imperial prestige | • Nadir Shah’s invasion (1739) • Ahmad Shah Abdali’s repeated invasions • Maratha expansion and conflict with Mughals |

| Stage 3 1761–1857 Rise of British Power | • British intervention in Indian politics • Mughal authority becomes symbolic • End of imperial sovereignty | • British victory at Buxar (1764) • Company gains Diwani rights • Mughals reduced to pensioners • 1857 Revolt & deposition of Bahadur Shah Zafar |

Timeline of the Decline of the Mughal Empire

| Period / Year | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1707 onwards (Post-Aurangzeb) | Decline begins after Aurangzeb’s death | Weak successors, court politics, jagir crisis, and administrative breakdown start showing. |

| Early to Mid-18th Century | Rise of regional powers (Marathas, Sikhs, Jats, Rajputs, Nawabs of Awadh, Bengal & Hyderabad) | Mughal authority becomes nominal; provinces become independent. |

| Increasing European Influence | British & French become active in Indian politics | Military modernisation and alliances with Indian rulers begin shaping power shifts. |

| 1739 | Nadir Shah’s invasion of Delhi | Mughal prestige collapses; treasury looted; Peacock Throne & Koh-i-Noor taken. |

| Mid-18th Century | Maratha expansion at its peak | Marathas become the dominant Indian power; reach Delhi and beyond. |

| 1757 | Battle of Plassey | British gain territorial control in Bengal; marks beginning of British political dominance. |

| 1761 | Third Battle of Panipat | Massive defeat of Marathas by Ahmad Shah Abdali; Mughal power becomes symbolic. |

| Late 18th – Early 19th Century | British consolidation (Subsidiary Alliance, wars with Indian states) | Mughal emperor reduced to a pensioner; British expand across India. |

| 1857 | The Great Revolt / First War of Independence | Bahadur Shah Zafar exiled; Mughal Empire formally abolished; India brought under direct British rule. |

Read More: Why Europeans Came to India?